Hogue pointed out an important aspect of the way the early English and European settlers viewed the landscape, they saw America as a wilderness-- both in terms of the natural environment and the people who had already settled there and cultivated the land--the Native Americans. In his article Hogue disusses the three types of wilderness that the early settlers faced: the physical wilderness of the land, the perceived spiritual wilderness of the native people and the psyhic wilderness of potential spiritual degration within the colonial Puritan mind.

Since the Puritans classified their new home as wilderness, they obviously saw the natural world as dangerous and something to be subdued. They also saw it, however, as a trial to be endured-- akin to the struggle of Moses in the desert, or to go to the source of the Christian idea of human versus nature, the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the lush, protected landscape of the Garden of Eden into the untamed world beyond.

After the American Revolutionary War, there was a shift away from viewing the land in a religious context to an agrarian ideal put forth by President Jefferson. The natural world was no longer seen as a wilderness to be feared, now it stood as what Hogue calls a "source and metaphor for the nation's status" and a "model of civic virtue and enlighted democracy." From then on, the landscape of America came to be seen in a moral and political context rather than a religious one.

In the 1830s, with the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a push to expand America's boundaries. From the original colonies (which make up a small percentage of the land in the contemporary U.S.), we pushed Westward to claim what was once French, Spanish and Native American land. It was Jackson that forced Native Americans out of their settlements in 1831 with his Indian Removal Act, the beginning of what would later be called The Trail of Tears.

It is this part of history that I find most disturbing-- while we're all familiar with the forced removal of Native Americans to Oklahoma and other reservations due to the American idea of Manifest Destiny; the catalogue and exhibition does a disservice to these native peoples by also excluding their artwork from the pages of their visual history.

Who are the most well known American landscape artists? In painting it's Thomas Cole and the artists of the Hudson River School and in photography it's Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter. From what I can tell from the plates of the catalogue, the exhibition presents a Euro-centric, male-dominated view of the American landscape. This led me to wonder how Native Americans image the natural world and how it differs from the European American view.

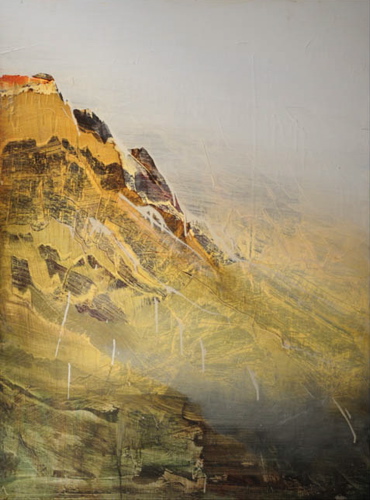

One contemporary landscape artist of Native American descent is James Lavadour, who is part Walla Wall and grew up on the Umatilla Reservation. He is known for his abstract landscapes inspired by mountainous northeastern Oregon. Like the abstract expressionist and action painters of the 1950s, Lavadour looks to painting as a kinetic expression of his physical experience with the landscape. He says this about his work: "At some point I made a connection between the ways walking conditioned my body movements and the way my body governed my hand when I painted. Links between muscle and memory, place and identity became the basis of my art."

"Little Bird" 2008, James Lavadour

Lavadour was part of a show titled "Off the Map: Landscape in the Native Imagination" that presented the work of five artists of native descent. The curator of the show, Kathleen Ash-Milby, described the native relationship to the land: " As a subject for Native artists, then, the land/landscape is laden with history and expectation. Land is home, culture, and identity, but it also represents violence, isolation, and loss." While European American representations of the landscape carry nationalistic and political associations, native American representations are often tied to identity and memory. I was surprised to find that these five artists also represent the natural world in a very abstract manner that seems to refer to a feeling about the landscape or a relationship to nature rather than attempting to represent a place. Ash-Milby explains this tendency: "The artists in Off the Map all use the landscape as both muse and subject, but none seek to represent a specific place you can locate in a guidebook or on a map. All landscapes, despite their intentions, are imaginary constructs, and these artists make no attempt to literally depict a specific place and time." Their work points away from a landscape demarcated by borders and boundaries and instead explore not only what we experience visually or physically but also how landscape becomes a part of the human psyche.

Artist Emmi Whitehorse, who was also included in the "Off the Map" show creates large, abstract multi-media pieces done on panel. Of Navajo descent, she references aspects of her culture in her work as well as memory and land. Water is also another prevalent theme, which she attributes to growing up in a desert climate. Whitehorse had this to say of her work: “My work is about and has always been about land, about being aware of our surroundings and appreciating the beauty of nature. I am concerned that we are no longer aware of those. The calm and beauty that is in my work I hope serves as a reminder of what is underfoot, of the exchange we make with nature. Light, space, and color are the axis around which my work evolves.” What's intriguing is that she thinks of the natural world in terms of an exchange between us and nature rather than one element theatening or dominating the other.

Contemporary native artists seem to draw inspiration from abstract expressionist artist George Morrison, who was of Ojibwa descent and was born on the Grand Portage Indian Reservation near Chippewa City in Minnesota. Above is one of his earlier, more representational paintings of the landscape. In the 1950s he became associated with a circle of abstract expressionists artists in NYC and thereafter his paintings dealt with similar themes and subject matter but was executed in this new style.

(Above, "Above Water" 2002 and Below, "Red Coral" 2007 by Emmi Whitehorse.)

Artist Emmi Whitehorse, who was also included in the "Off the Map" show creates large, abstract multi-media pieces done on panel. Of Navajo descent, she references aspects of her culture in her work as well as memory and land. Water is also another prevalent theme, which she attributes to growing up in a desert climate. Whitehorse had this to say of her work: “My work is about and has always been about land, about being aware of our surroundings and appreciating the beauty of nature. I am concerned that we are no longer aware of those. The calm and beauty that is in my work I hope serves as a reminder of what is underfoot, of the exchange we make with nature. Light, space, and color are the axis around which my work evolves.” What's intriguing is that she thinks of the natural world in terms of an exchange between us and nature rather than one element theatening or dominating the other.

Contemporary native artists seem to draw inspiration from abstract expressionist artist George Morrison, who was of Ojibwa descent and was born on the Grand Portage Indian Reservation near Chippewa City in Minnesota. Above is one of his earlier, more representational paintings of the landscape. In the 1950s he became associated with a circle of abstract expressionists artists in NYC and thereafter his paintings dealt with similar themes and subject matter but was executed in this new style.

I was disturbed by the lack of Native American art as well. It was like they were still being excluded. There was nothing to show or suggest how we might start to reconcile the problem. If we're supposed to be striving toward some sense of responsibility, I don't think the show did that visually.

ReplyDelete